![]() |

| Salvage efforts at the crash scene: photo source unknown. |

When did the airplane first become the tool of terrorists? Some put the date as early as Feb. 21, 1931, when armed Peruvian revolutionaries attempted to force the pilot of a Ford Tri-Motor to carry them aloft to drop leaflets. But the pilot refused and the flight never took place, so it's hard to assign great significance to this event.

Others could point out that warring nations have long employed aircraft to instill fear in civilian populations. Certainly the airborne destruction of Rotterdam ordered by Hermann Göring in 1940, to cite a single example, could be nothing but terrorism.

Jangir Arasly, in a paper for the Partnership for Peace Consortium, suggests the era of "modern aviation terrorism" began as late as 1968 with the hijacking of an El Al jet by gunmen seeking to spotlight the Palestinian cause.

But to Cuban-born historian Manuel Márquez-Sterling, it was the seizure of the Cubana de Aviación Viscount bearing tail number CU-T603 on Nov. 1, 1958, that introduced "a terrorist tactic that would endure."

From this came all the other hijackings for attention and political gain, a bloody trail leading to the day in September 2001 when four captured airliners would slam into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania, killing nearly 2,800 people.

In the years since, few topics have so gripped the world as the struggle with extremism and the ever-present fear of future attacks.

Yet in 1958, for the American authorities confronted with the armed takeover and subsequent crash of a flight from Miami. there was not even a vocabulary with which to describe such an event. Hijackings were something that happened to truckloads of whiskey, and as journalist Geraldo Reyes has observed, "the closest word (to) terrorism was sabotage."

As the U.S. sought to make sense of the hijacking, telegrams flew between the State Department and the American Embassy in Havana, and Ambassador Earl T. Smith dispatched a vice-consul to eastern Cuba to interview the three passengers who were the only known survivors.

It soon emerged, however, that three additional people aboard the flight, all hijackers, had also lived through the crash. Passenger Osiris Martinez, who was rescued by a villager in a canoe, remembered seeing two men crawling along a wing that protruded from the water.

One of the surviving gunmen was identified as Edmundo Ponce de León, a Cuban-American who had served in the U.S. Air Force and was said to have been the ringleader of the Viscount attack.

In the end, however, the U.S. would not pursue Ponce de León or the others involved in stashing weapons on the plane and commandeering it. The State Department reportedly asked the Department of Justice to launch an investigation, but federal prosecutors in Miami were said to have determined that the case was outside their jurisdiction – this despite the Florida origin of the flight and the U.S. citizenship held by several of the passengers, and despite even the apparent planning of the crime on U.S. soil.

Would the decision have been different had the hijacking involved, say, one of Pan Am's new jet flights between New York and London? Certainly there's a sense that the seizure of CU-T603 was regarded more as an example of Latin America's near-constant strife than a crime touching the United States. News accounts invariably referred to the U.S. citizens on the flight as "naturalized Americans" (which wasn't even true: Osiris Martinez's wife and three small children, all killed in the crash, were American-born).

But there was more at play than attitudes. The U.S., watching the mounting instability in its island neighbour, had been quietly working through 1958 to find a "middle way" between dictator Batista and the Marxist-oriented Castro movement. Any overt attempt to intercede in Cuban affairs could derail these efforts.

As it turned out, there was no middle ground. Just two months after the hijacking, Batista was gone, boarding an airplane in the night for the Dominican Republic with his family and friends and a fortune said to be in the hundreds of millions.

As the world watched Castro make his triumphant entrance into Havana and begin to set in place his communist government, the events of Nov. 1, 1958, receded into the past.

But they were not forgotten.

*

Half a century after the takeover of the Viscount, a startling report began to circulate among South Florida's Cuban community. Edmundo Ponce de León, alleged organizer of the hijacking of CU-T603, was said to be living in Miami – living, in fact, not far from relatives of victims of the crash.

Ponce de León, now going by the first name of "Freddy," had slipped back into Florida in 1994, apparently no longer enamoured with communism and by then anxious to escape the hard times that descended on Cuba after the Soviet collapse. Whether the U.S. authorities knew the details of his past is unknown, but he was able to live quietly in Miami until 2008. Then he became involved in a property dispute with his sister, and her lawyer contacted survivors of the crash.

![]() |

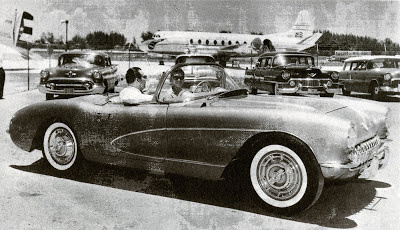

| Ponce de León, 2011: NBC image |

With the scars of 9-11 still fresh and the Cuban-American community pressing for action, U.S. officials would not drop the cast so quickly this time. Ponce de León, however, denied any role in the hijacking, claiming he had been merely a passenger and after the crash was taken prisoner by the rebel forces.

Without Cuba's co-operation and with only the 50-year-old recollections of witnesses with which to refute his claims, the U.S. Attorney's Office announced that Ponce de León would not be prosecuted.

That did not mollify members of the Cuban community. Denied satisfaction from the government, they turned to the press. NBC Miami began an investigation, even filming Ponce de León in his small apartment, where his wife revealed that he had terminal cancer and the accused hijacker himself would say only: "It was 50 years ago."

On Oct. 3, 2011, just hours before NBC was to air the first installment of its report, Ponce de León died in a Miami hospital. He was buried in a U.S. veterans' ceremony with military honours.

Perhaps to avoid embarrassment, the government had reopened its investigation as the television report was being prepared. Now, their suspect dead, the authorities said Ponce de León had confessed to his part in the hijacking."We were in the process of seeking justice," a FBI spokesman told the television network.

The survivors, and the descendants of the passengers and air crew who died in the crash, said the confession was not all they had wanted, but it was enough. Five decades after the shining airliner fell into the Bahia de Nipe, taking 14 lives and introducing a new and ferocious weapon of fear, the story of CU-T603 was over.

Sources and further reading:

Vickers Viscount Network

Daytona Beach Morning Journal, Nov. 3, 1958:"Rebel Seized Plane Crashes"

Toledo Blade, Jan. 2, 1959: "Castro Forces in Complete Control in Cuba"

Jules Dubois, Fidel Castro: Rebel: Liberator or Dictator? Bobbs-Merrill, 1959.

Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files: Cuba Internal and Foreign Affairs 1955-1959

Diplomatic History, January 1996: "The Caribbean Triangle: Betancourt, Castro and Trujillo and U.S. Foreign Policy, 1958-1963," by Stephen G. Rabe

Partnership for Peace Consortium, 2005: "Terrorism and Civil Aviation Security: Problems and Trends," paper by Jangir Arasly

Miami Herald, Oct. 26, 2008, "Cuban Hijacking Survivor's Grief Tinged with Regret"

Washington Post, Nov. 19, 2008: "Was 'Passenger' on Downed Flight a Hijacker?"

NBC 6 South Florida, Oct. 13, 2011: "Alleged Cubana Hijacker Dies"

NBC 6 South Florida, Nov. 2, 2012: "Ponce de Leon Admitted Role in Cubana Hijacking: FBI"

Cuba 1952-1959

Cuba Y La Masoneria